By Pamela Dorazio Dean

For over a year, I’ve been participating in the National Museums and Cultural Institutions Committee formed by the Conference of Presidents of Major Italian American Organizations. This committee grew out of a plan activated by COPOMIAO and ISDA National President Basil M. Russo to unite Italian Americans across the United States through initiatives surrounding public policy, youth engagement, education, and, in my case, history and ancestry.

As Curator of the Western Reserve Historical Society of Italian American History, and Director of the Italian American Museum of Cleveland, I have found that regular collaboration with these peers has proved invaluable, because, in history, there’s always another story to tell, to learn, to expand on, to deepen.

The vital role that each of these organizations and institutions play in the preservation and perpetuation of Italian American heritage and culture cannot be understated. The new generations of Italian Americans are further and further removed from the immigrant ancestors who set the foundation of our culture. These generations no longer live in areas populated with other Italian Americans. By providing a physical gathering place and collecting and preserving the “stuff” of history, museums and cultural institutions serve as the community’s memory center and, in a sense, become an ethnic corridor where people can come together and open new doors to Italian America’s history and culture.

To inspire people during Italian American Heritage Month to reflect upon their ancestry, and to instill a greater understanding of the important work that these organizations do, I reached out to a pair of my colleagues on the Museums and Cultural Organizations Committee, Melissa E. Marinaro, Director of the Italian American Program at the Heinz History Center, and Marianna Gatto, Executive Director of the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles.

I asked them to select one artifact from their collection and share its story. I also included something from the WRHS Italian American Collection. Without these institutions and the individuals who run them, these materials, which convey volumes about our history and culture, would be hidden away, not publicly accessible, or worse, lost forever. Here are three rich and impactful stories. Share them with your family, and perhaps share a few more while you’re at it, because in the end, all our stories, big and small, serve to elevate our cultural identity and deepen the Italian American experience.

The Italian American Museum of Los Angeles: The Making of an Enemy

Submitted by Marianna Gatto, IAMLA Executive Director

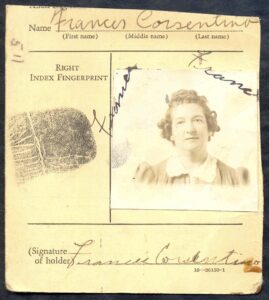

The enemy alien registration card that belonged to Los Angeles resident Frances Corsentino is an important artifact not only for Italian Americans in California, but to the national Italian American community as well. It relates a story of past discrimination against Italian Americans and creates an understanding of how it negatively impacted Italian American culture in the ensuing decades.

Following the entry of the United States into World War II, Los Angeles resident Frances Corsentino was among the 600,000 Italian Americans who had not yet naturalized and whom the U.S. government labeled as “enemy aliens.” In 1942, these enemy aliens were ordered to register with the government at their local post office. They were fingerprinted and given enemy alien identification cards, which they were required to carry at-all-times or face severe penalties.

Frances, who had lived in the United States for years, waited with her three American-born children in a line that wrapped around the block. She complied without question, yet Frances felt anxious. There was nervous chatter among some of those waiting, while others were silent and stoic. Frances overheard murmurings of more restrictions and mass arrests, and her anxiety turned to dread. This requirement had such an effect on Frances that she refused to throw out the enemy alien I.D. even decades later.

In the months that followed, thousands of Italian Americans were forced to leave their homes and to surrender property ranging from radios to fishing boats. They were subject to curfews and travel restrictions. Approximately 2,000 Italian Americans, including some who had become naturalized citizens, were arrested, and approximately 400 were sent to internment camps without being charged with a crime or allowed legal counsel.

What Italian Americans experienced pales in comparison to the government’s heinous treatment of the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from their homes during the war. Yet, the impact of the enemy alien restrictions cannot be understood simply by the number directly impacted. Classifying people as enemies, not for what they had done, but for their nationality, had lasting effects not only on those deemed enemy aliens, but on their descendants, as well. For the Corsentino family, like many Italian Americans, the greatest loss was cultural.

In addition to being labeled as undesirables, Italian Americans were also encouraged not to speak the Italian language as it was deemed the “enemy’s language.” As a result, the number of Italian-speaking households in the United States declined by half in the decades following. This started a trend amongst Italian Americans whereby they began to distance themselves from their heritage and adopt more “American” identities. This became even more widespread in the post-World War II era of consensus and conformity.

Western Reserve Historical Society: Columbus and the Winding Path to Assimilation

Submitted by Pamela Dorazio Dean, WRHS Curator for Italian American History/Director of the Italian American Museum of Cleveland

The earliest Christopher Columbus Day event was held in 1892, as revealed by a review of The Plain Dealerarchives. On the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ 1492 voyage, President Benjamin Harrison issued a proclamation that the United States would mark the occasion as a holiday. Following this, cities across the country, including Cleveland, organized events and parades. Many scholars suggest that Harrison also used the anniversary celebration as a gesture to improve diplomatic relations with Italy and the Italian immigrants living in the U.S. after the horrific lynching of 11 Italian immigrants in New Orleans in March 1891.

Not until the 1910s is there another mention in The Plain Dealer of a city-wide Columbus Day celebration in Cleveland. For a decade prior, however, Italian immigrants had observed Columbus Day on a smaller scale in their own neighborhoods. Echoes of the New Orleans lynching and the discrimination the Italian immigrants faced in their everyday lives inspired them to celebrate Columbus, who was one of their own countrymen. Expressing pride in Columbus allowed the Italian immigrants to publicly express pride in their culture, and served as a way to legitimize their presence in the U.S. to those who otherwise thought they did not belong in the country.

In 1910, Columbus Day was declared a legal holiday in the state of Ohio, primarily due to the efforts of Giuseppe Carabelli. Carabelli was a leader in Cleveland’s Italian immigrant community. He was the first Italian American to serve in the Ohio House of Representatives and was the proprietor of The Carabelli Co., a stone carving and sculpting firm located on Euclid Avenue, opposite Lake View Cemetery. On October 12, 1910, a grand celebration of Columbus Day was held in Cleveland, organized by a committee comprised of both Italian Americans and city leaders. The day was marked with a large parade on Euclid Avenue in downtown Cleveland that ended with a grand banquet sponsored by the Knights of Columbus at the Hotel Hollenden.

The Columbus Day Parade continued to be held annually in downtown Cleveland until 2004 when the committee in charge decided to move it to Little Italy.

Click here for this year’s details on Cleveland’s Columbus Day Parade.

Senator John Heinz History Center: Pittsburgh’s Faithful Find Solace in San Rocco

Submitted by Melissa Marinaro, Director of the Italian American Program

San Rocco is one of the most iconic artifacts in the Heinz History Center’s Italian American Collection. The object itself is a religious icon and its history recounts an important Italian American community of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

San Rocco, also known as Saint Roch, was a 14th-century French saint who took a vow of poverty and contracted plague-like symptoms while on a pilgrimage to Rome. During his affliction, he became an outcast and was forced to seek refuge in a cave where his condition worsened. While in exile, an angel appeared to San Rocco, healed his wounds, and a small dog nursed him back to health by bringing him loaves of bread. In Italy, San Rocco is a popular patron saint, and many villages celebrate his feast day in August.

Italian immigrants brought their tradition of venerating Catholic saints to their new homeland, replicating processions and festivals in the United States. This painted plaster sculpture of San Rocco was brought to Pittsburgh in 1931 by Joseph Costa, who founded the San Rocco & St. Anthony Society. Costa traveled back to his hometown of Maierato in Vibo Valentia province (Calabria) to acquire the icon to reproduce the religious procession for his countrymen living in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of East Liberty. This statue was paraded annually from 1931-1961 following a mass at Our Lady Help of Christians Catholic Church.

East Liberty was home to Larimer Avenue, Pittsburgh’s Little Italy until the 1960s, which was when the city underwent an urban housing renewal that engendered the Italian community’s transition to the suburbs. Before that period, Larimer Avenue thrived — it was a destination for Italian immigrants from the North and South of Italy and had a vibrant commercial district with grocery stores, bakeries, and butcher shops that catered to Pittsburgh’s Italian community at large. It was also home to multiple mutual aid societies and social clubs. L.A., as it was known to its residents, still looms large in the living memory of the Italian American community of Pittsburgh.

Italian Sons and Daughters of America is a proud member of The Conference of Presidents of Major Italian American Organizations. COPOMIAO is comprised of 58 of the most influential cultural, educational, fraternal and anti-defamation groups in the nation.

Make the Pledge and join Italian Sons and Daughters of America today.